Epigenetic clocks — A test to measure how fast you age

Why quantifying aging is a prerequisite to life extension

Hi friends 👋

Welcome to Health & Wealth — your weekly source of the latest health research and biotech trends. I stepped back from writing last week to prioritize personal learning and health.

In lieu of what I had planned this week, I’m revisiting my inaugural post on epigenetic clocks. Many of you joined along the way and may not have come across this piece. There have since been new commercial entrants and pre-print papers that I haven’t had a chance to thoroughly review yet. Let me know what I should look more into. Happy reading!

Article Highlights

Epigenetic clocks are a way to estimate your biological age, which can be different from your chronological age (number of years since you've been born).

Having a reliable way to measure aging is critical for researchers to develop effective anti-aging drugs and for individuals to slow down and reverse their own aging process.

The emergence of epigenetic clocks, while still in their infancy, is not fringe science. Current tests like the Index Test and myDNAge are version 1.0 based on work from key scientists.

More predictive epigenetic age tests are being developed and will make age testing more common in the consumer market.

When you think of the field of aging, you might immediately think of the quest to discover the fountain of youth — a drug to slow down or reverse aging. But what most people don't ask is the question that comes before that: how do you know whether an intervention actually works?

Enter: epigenetic clocks.

The "epigenetic clock" was first introduced in 2013 by Dr. Steve Horvath as a way to estimate biological age. But the concept remains grossly underrated. So, where are we now, what are the current gaps, and what's to come?

In this post, we'll cover how:

Not everyone ages at the same rate

Biological age can be estimated with epigenetics

Why a standard way to quantify aging is critical

What aging tests you can buy now

Whether these tests are worth your money

What's to come

Not everyone ages at the same rate

Every year, whether you want to or not, the calendar tells you you're a year older. But not everyone ages at the same rate. Some people's bodies actually age slower (or faster) than others.

This is the difference between chronological age and biological age. For example, you may be 35 years old but have a biological age of 30.

Estimating biological age with epigenetics

A way to measure biological age is through a type of clock based on the methylation patterns of your DNA. Methylation is when methyl groups are added or removed on specific sites (called "CpG islands") along the DNA. These methyl groups are like ornaments on a Christmas tree and impact how and when genes are turned off or on. As you age, the methylation patterns can change in a predictable way — like clockwork.

There are a lot of CpG sites in the human genome. About 28 million. The goal of developing a robust aging clock is to pick out the relevant sites and weigh them according to their perceived importance to generate a biological age estimate.

(If you're familiar with the genetics space, the idea is kind of similar to a polygenic risk score. The prediction value of epigenetic clocks depends on the weighted aggregate of individual CpGs. So what a polygenic risk score is for the genome, the epigenetic clock is for the epigenome.)

The first version of the Horvath Clock showed that predicted epigenetic age is within 3.6 years of study participants' chronological age. But there are outliers. Centenarians (105+) have an average epigenetic age that is 8.6 years younger than their expected chronological age. What this tells us is that some people's clocks appear to be ticking slower.

A standard way to quantify aging is critical

You might think this is some obscure science quirk, but not so: the success of the aging field critically depends on having an accurate way to quantify aging.

Without a measuring stick, we can't know what works.

Not being able to accurately and quickly estimate biological age means we can't validate aging interventions that may slow or reverse aging in humans. It's equivalent to trying to manage diabetes without an easy way to measure blood sugar levels. Without feedback, we fly blind.

While the ultimate endpoint for all of us is death, that's too long of a timeframe. We have much longer lifespans than mice used in animal studies. So we need to use biomarkers as proxy endpoints for studying aging (for either academic research or N-of-1 self-experiments). The question is: what specific set of biomarkers will we converge on to measure aging?

Dr. Steve Horvath himself recognizes that the driver for establishing a consensus is through capitalism. In a recent talk, he remarked:

"I believe that companies that use effective biomarkers of aging will succeed at developing effective anti-aging interventions. Success will ultimately lead to emulation and adoption."

What aging tests you can buy now

The emergence of epigenetic clocks, while still in their infancy, is not fringe science. On the contrary, the two commercially available tests I will mention are directly based on work from two key scientists who shaped this field, Dr. Steve Horvath and Dr. Morgan Levine.

By now, there are many different published versions of epigenetic clocks, all trying to approximate the same signal of aging. The good news is, like each successive version of the iPhone, they are generally getting better over time.

To briefly describe the current state of research:

The first-generation clocks were trained to predict chronological age. The second-generation, which include the 'GrimAge' and 'PhenoAge' clocks, were trained against the physical effects of aging (including blood-based proteins). This makes second-generation clocks better suited to estimate time-to-death and the risk of age-related diseases like heart disease, cancer, and menopause. As Levine's paper on the PhenoAge clock explains:

"Using chronological age as the reference [as is the case of first-generation clocks], by definition, may exclude CpGs whose methylation patterns don’t display strong time-dependent changes, but instead signal the departure of biological age from chronological age. Thus, it is important to not only capture CpGs that display changes with chronological time, but also those that account for differences in risk and physiological status among individuals of the same chronological age."

Index Test by Elysium Health

Anti-aging company Elysium Health launched its $499 at-home Index test in November 2019. Index is based on Dr. Morgan Levine's work developing the PhenoAge clock in 2018. Levine was a former postdoc at the Horvath lab, now a professor at Yale and Elysium's bioinformatics advisor.

The Index Test uses an Illumina-based methylation array that measures "over 100,000" CpG methylation sites. However, it's unclear how much of that is actually used to generate the Index report, since the PhenoAge clock included only 513 sites in its model.

Among all of the commercially available epigenetic clocks, it appears the Index test performs the best. Levine's involvement is a strong vote of confidence on Index's science. It's also the only test explicitly commercializing a second-generation clock (PhenoAge).

Some caveats: publicly available details on their science are still scanty, and the company has been criticized for using its advisory board's credentials as window dressing for their marketing. It's understandable for their product to still be a work in progress, but hopefully, they continue to improve and refine over time.

myDNAge by Epimorphy (Zymo Research company)

The $299 myDNAge consumer test has been available since around 2017. MyDNAge is based on the first version of the Horvath clock developed in 2013, which Zymo Research gained exclusive license to commercialize.

While the original Horvath clock included 353 CpG sites, the company added more age-related sites. The test analyzes over 2,000 sites, which claims to have improved the median test error of age prediction from 3.6 years down to 1.9 years. While this sounds impressive, first-generation clocks run the risk of overfitting against chronological age. This tradeoff may overlook differences that indicate actual physiological changes of aging.

I imagine there are licensing limitations (exclusive licenses to second-generation clocks have been given to a life insurance company?); otherwise, it would have been really cool to see myDNAge iterate to use the latest 2019 GrimAge model. Their first-mover advantage may turn into a disadvantage as more predictive tests with stronger brand messaging eclipse them.

Are these tests currently worth your money?

Yes and no. Epigenetic tests provide a way to tangibly estimate something that was previously unknowable. You can regularly test to compare results over time and track how lifestyle changes impact your rate of aging.

But so far, clocks are not validated for individual use. Instead, they were developed by looking at trends across large studies.

There are also serious concerns about the reproducibility of results. A recent 2021 pre-print article led by Levine found results varied widely when analyses were rerun with the same samples. The study reported deviations of 3 to 9 years from the same sample for 6 major epigenetic clocks. This is a big problem! That means if a treatment can reduce epigenetic age by 2 years, technical noise of 8 years can completely mask this effect. You might then conclude that the intervention doesn't work. Conversely, you might be feeling pretty good about yourself having a biological age that's lower than your chronological age. But is that true biological variation or just noise? Might want to rerun your sample before you start gloating.

It's not all bad news, however. The pre-print article goes on to describe a novel computational solution to minimize random noise. For example, the PhenoAge had a median deviation for the same sample of 2.4 years (maximum 8.6 years). Applying the new computational model smoothed out those fluctuations — median deviations of the same sample were within 0.6 years (maximum 1.6 years).

What's exciting is that Levine shared in a recent podcast (timestamp: 39:45) that Elysium will provide improved versions of past tests to customers. What that sounds like is this method Levine's group described will be used to reduce technical variation in upcoming Index reports.

The bottom line: current tests can be worth it if you're an early-adopter into collecting biometric data. If you buy, take the results with a grain of salt and understand this is version 1.0. Third-generation clocks are coming very soon and will make age testing more common in the consumer market.

What's to come

This is just the beginning of epigenetic age testing. Even more predictive epigenetic clocks are being developed, and more commercial players will join. For example, it looks like Dr. David Sinclair, a high-profile Harvard aging professor, will be soon stepping into the age testing arena:

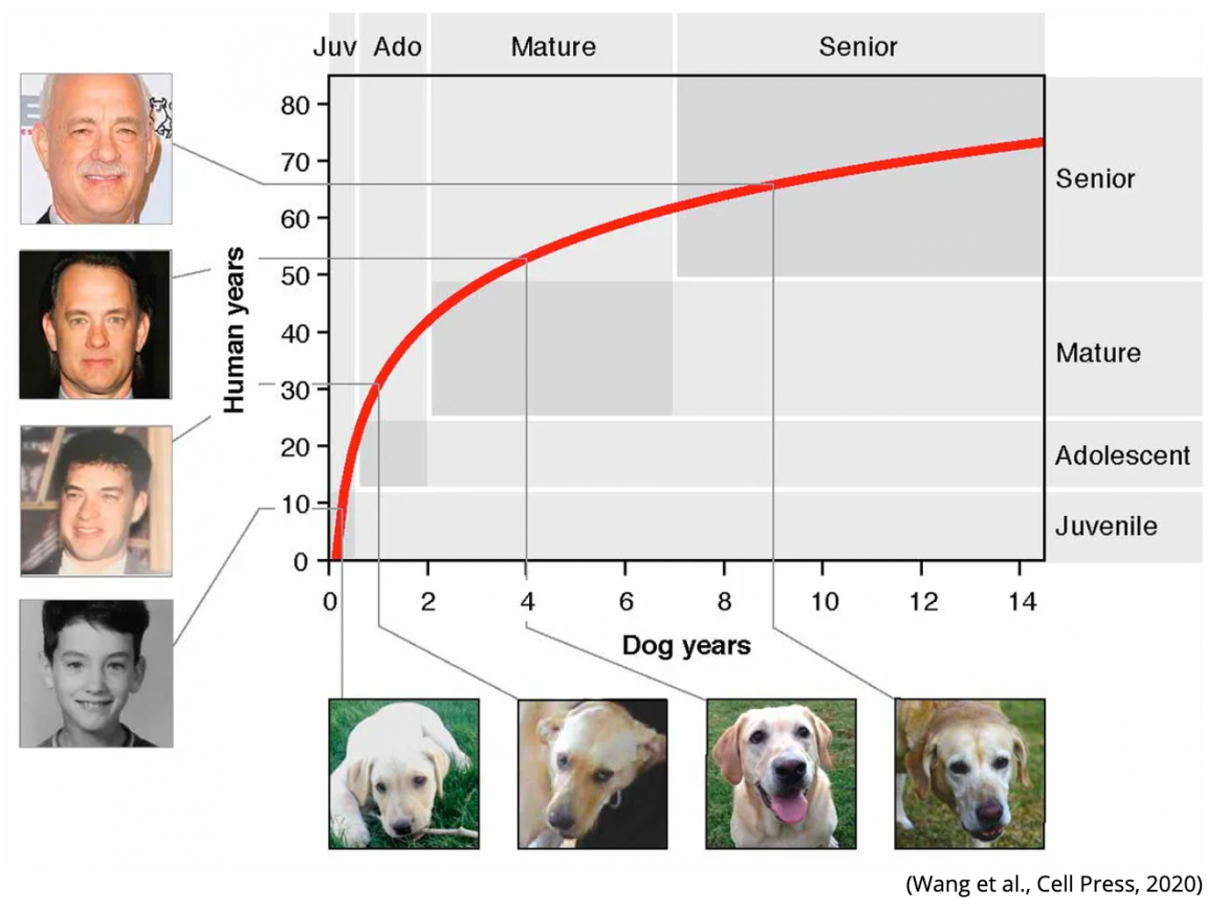

Epigenetic clocks can also be used across different species like mice, dogs, and humans. So age in "dog years" can be translated into "human years" to interpret the significance of animal studies for humans:

As we move towards a standard way to quantify aging, we can personalize strategies to slow down or reverse our aging process. Applications of a reliable aging clock include:

Provide tighter feedback loops for individuals to see if certain lifestyle changes are indeed slowing (or accelerating!) their aging process.

Speed up aging drug development by using biomarkers to evaluate efficacy in clinical trials.

Identify new aging targets specific to DNA or epigenetic changes that can impact aging.

Define the aging process during the earliest stages of life (embryogenesis) to mimic similar rejuvenation in adult cells.

Age reversal is a lot closer than you might think. And it starts with being able to accurately tell time.

Addendum: Josh Mitteldorf on epigenetic clocks

Josh writes a fantastic blog on aging and recently wrote about principal component analysis clocks, which I mention above. Here are some of his comments and answers to two questions I asked him, reproduced below.

“You might mention some of the other companies that do methylation testing. I'm working with Tru Diagnostics, and there's EpiAge and several others competing in this market. When I write, I emphasize my belief that aging has an epigenetic basis, which makes me more inclined to have faith in clocks based on epigenetics rather than blood pressure or inflammation markers or grip strength, etc.”

Besides improving predictive ability, what are the key challenges in commercializing epigenetic testing for individual use that need to be addressed?

“Up until now, the clocks haven't been accurate enough to be useful on an individual level. Too much random scatter. But that might be changing, especially with the PCA clocks. Then the challenge will be, "what can I do about it?" Dr Kara Fitzgerald proposes an answer. There's room for a lot more built on her MDL program as a start.”

Do you think there will be other more accurate and/or more accessible ways to estimate biological aging beyond using epigenetic markers?

“I have faith in epigenetic clocks because I believe that epigenetic changes are the cause of aging. But there are clocks based on the proteome, the microbiome, and the immune system, and time will tell if these prove to be better predictors of all-cause mortality.”

My promise to you is that I would respect your time by providing high-quality, valuable insights. I only write what I would personally enjoy reading from others. As such, each essay takes dedicated time and brainpower to research and write. If you have thoughts on how to better engage with you and present my ideas (format, cadence, style), please reach out.

If you’re finding this content valuable, consider sharing it with friends or coworkers!

Thanks for reading!

Christina